Guided notes keep kids engaged and on-task. But are students just coloring by number? Can guided notes ever help them to develop into a version of Bob Ross?

I’d like to share with you a novel way to create and use guided notes in math class. There were very good reasons I started using them as a brand-new teacher and very good reasons why I moved away as I outgrew them. Recently, I’ve decided to give them another chance.

In this article I’d like to explore why they worked early on, why they stopped being an effective tool for me (and many other teachers), and what adjustments have been made in their design and implementation that offer access to the “best of both worlds.”

Why Use Guided Notes

There are a lot of positive outcomes of using guided notes the way I used to use them. Student engagement, for example, is a lot easier to entice with guided notes. And, to a passing administrator counting how many kids are “on-task,” at any given moment, things look AWESOME.

Another benefit of guided notes is that students have an organized record of what was learned. When a kid is stuck on homework or a problem in class, a viable support is their notes (because they’ll make sense). Providing guided notes to absent students, or via distance learning is another great benefit of using them. And at the end of the course, students can have an entire “workbook,” that captures all of the learning throughout the class.

These positives are for the students. There are plenty of gains for teachers as well. At the beginning of my teaching career, I created and used guided notes for nearly all my lessons. The structure the notes provided was as much for me as it was for the students. Essentially, the guided notes were my lesson plans structured in a format for the student. They could follow along and fill in the blanks, write formulas in appropriate spots, write steps, and show work in a structured fashion.

The Trade-Offs

If you’re a guided notes user, this might be a bit prickly. But, in my experience, guided notes are not a total win, there are some negatives. Even if you disagree, hear me out.

To start this line of thinking, let’s begin with an extreme. Why don’t most students just learn from the textbook? All of the required structure and clarity are there, right?

Guided notes can provide too much structure for students, requiring them to not think as much or as deeply. Learning is hard. Our job as teachers is not to make learning easier, it’s to make the level of difficulty appropriate for the student. Creating intrigue is part of a learning experience.

Students often love guided notes because they absolve students of the responsibility of identifying what’s most important, prioritizing, predicting what’s next, or connecting what they learned yesterday to today. In short, they have less to think about. Navigating the mystery that an appropriate amount of ambiguity provides is part of the learning experience for students.

There’s one more, difficult to state, negative that I’d like to explore. To facilitate this line of thinking, let’s talk about bowling.

In bowling, a ball is rolled down a lane towards a collection of 10 pins. The objective is to knock down as many pins as possible. On each side of the lane is a gutter. If the ball rolls into the gutter, the pins will remain standing safely.

Too little structure in a lesson is like trying to bowl without a lane. Too much structure is like placing bumpers in the gutters. The bumpers prevent the ball from falling into the gutter, ensuring that at least some pins get knocked down, regardless of the skill of the player.

Our job as teachers is not to help kids get good grades and the right answers. Good grades and right answers are evidence that we have done our job well. Our job is to help students develop knowledge and ability.

Guided notes can be too restrictive and kill creativity and original thought. This can stifle a lot of students, especially those who are both creative and intelligent. An overly structured lesson can hamper student learning just like an unorganized lesson can. The insidious aspect of this is that well-intentioned teachers often never see the negative consequence of their structure.

I would imagine that any teacher who’s been in a school for a few years will run into a situation where a former student of theirs, one who performed well in their class, is now reported to know very little and is underperforming. There are a lot of reasons this can happen, but one of them is the possibility that what was taught wasn’t authentically learned. There were bumpers in the gutters the whole time!

If you have ever had the privilege of following a group of students through multiple courses the difficulty of developing retention and transfer of skill and knowledge will be one of the first hidden challenges you’ll face. We have all seen students that memory dump from one topic to the next. We’ve had the kids that look at the study guide for the final exam and react as though they had never seen this before, even though they performed well. That situation is exponentially amplified over time, but we don’t usually get to see it directly. It’s there and too much structure perpetuates it!

Structure is needed, like water. But we’re not amphibious!

Using Guided Notes – An Example Lesson

I am a believer in employing the Socratic method of teaching whenever the chance presents itself. If a lesson can be delivered in a way that a question is being explored and it feels like a conversation, with lots of back and forth between students and teacher, it will be a powerful learning experience.

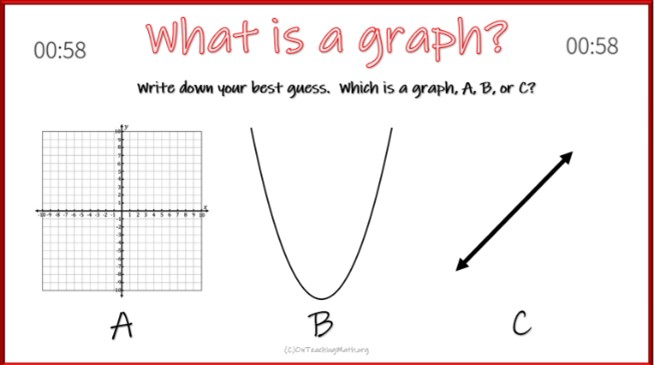

Here’s an example. One of my classes is Algebra 1. We are beginning a unit on quadratic equations. I start the unit with a question, What is a graph? (You can see a video lesson here, and download a copy of the guided notes described in this article here.)

You can see a GIF of a one-minute timer that starts automatically in the top right and left corners. This is a great addition that adds urgency for students without me having to do anything more than copy and paste it into a slide. If you’d like to download the GIF, you can do so here.

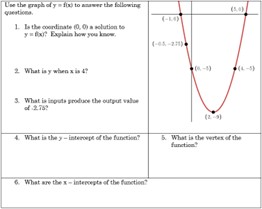

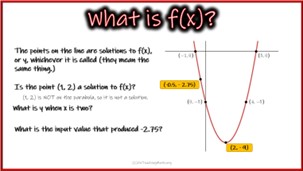

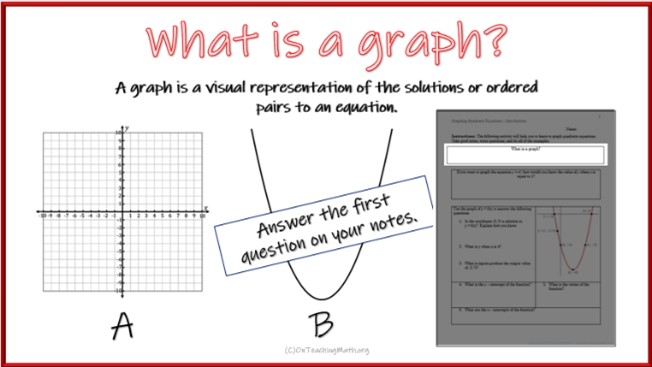

Students discuss which they think is correct, the coordinate plane, the parabola, or the line. In the lesson, the parabola, and then later the line, slide over the coordinate plane making a graph. The purpose of the entire lesson is to drive home the idea that a graph is a picture of all the solutions, coordinates, or order pairs, from an equation (in this context). The parabola is the shape made by a quadratic equation and its features are consistent for all quadratic equations. That point is very difficult to drive home through straight lecture. But, questioning and discussion allow students to play around with the ideas.

After discussion, the students are prompted to write about their learning. The “answer,” is never written on the board. I post an image of their guided notes highlighting exactly where they need to be. This might seem a little too focused, but if students are busy engaging with the lesson, the guided notes will have been lost for a moment!

The lesson and the guided notes are designed to work together and share identical sequencing. However, they do not share identical examples. Sometimes the problem in the lesson is the same as in the notes, but often the lesson and notes will have different examples, allowing students to try what they’ve learned without copying.

The questions in the lesson are explored through a variety of methods. In the picture below on the right, you can see a screen capture of the lesson. Each question comes up individually and is explored with whatever method seems most appropriate at the time. When finished with the slide, students are then given time to explore the questions in the guided notes. The questions are similar, but not identical. This way students are thinking and writing, not just acting as 21st-century scribes and copying information from the board onto their paper mindlessly.

Another change in guided notes is the addition of plenty of what test writing professionals call “white space.” There is a lot of space to write allowing students to record questions, scratch work, and ideas on their notes spontaneously, regardless of our original design and intent.

I encourage students to write their observations and ideas down on their notes, and set up “discoveries,” to meet this end. Here’s another example in this same lesson.

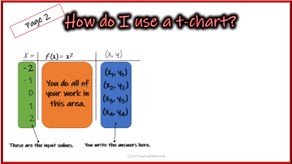

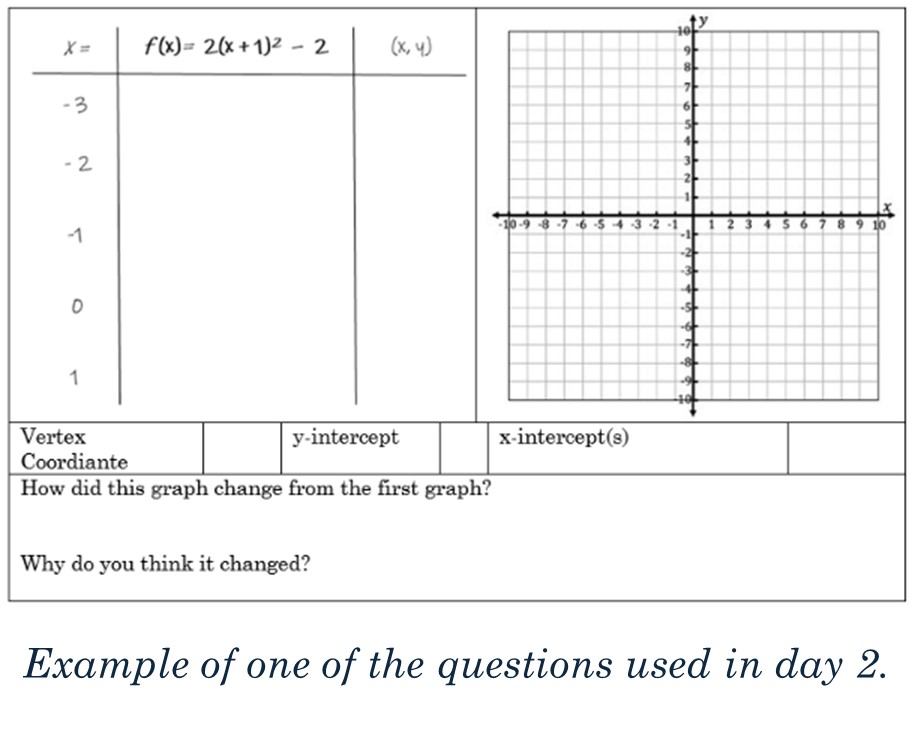

From the next images, the left is a copy of the guided notes. The right side shows a screenshot from the lesson. The example is the same in both, and it is expected that students will follow along and do the work step by step at first, then will try an increasingly larger chunk of the work independently. That’s not too novel of an idea, but what is also done is that later, students are encouraged to return to this part of their notes and record more notes when we review their practice work. That’s the purpose of the extra space on the sides of their t-chart. This is encouraged when we review the homework, which is shown below the slide from the lesson’s slide titled How do I use a t-chart?

Practice and Learning

Instead of homework on the first day of the unit, I try to set up a short lesson like this one and then give students accessible, but not too easy, questions that can be completed in class. The questions are included in their guided notes. As before, there’s plenty of white space for students to write notes, and questions, explore with scratch work, or whatever else they might like to do.

The second day of the lesson begins with a thorough review of the two questions. Students are encouraged to reflect on their performance. Did they mess up? If so, why? How can we use the notes to promote improvement? After all, messing up is part of learning.

This process does a couple of things. First, it gives students opportunities to revise their notes, but also familiarize themselves with the notes. What comes next is some structured practice.

There are four questions, each slightly different and more difficult than the previous question. In their groups (if appropriate), students are given ten minutes to work on the first question. They use their guided notes to navigate confusion and refine procedures. After the ten minutes is up, in the same fashion in which the lesson was delivered, the first question is reviewed. Students are encouraged to reflect and write, to record their learning on their paper.

The process is repeated for the remaining three questions. In the end, the practice done in class becomes part of their notes, a set of worked examples.

On the third day, independent practice is taken on. Students are given ten minutes per question, just like before, but are working alone and referring to their notes. After they work alone will be given a few minutes to collaborate and ask questions, and then a few minutes will be spent on whole-class discussion.

The fourth day is a check-for-understanding assessment. Open notes are appropriate at this point. Students are still learning the content, but are also learning to effectively take and use notes. By allowing them to refer to their notes here good note taking is encouraged.

In Review

A few quick tips to consider when making guided notes.

- If the information needs to be copied correctly by the student in the notes, just leave it in the notes.

- The skill of good note-taking in math class rarely overlaps with being a scribe.

- Add formulas and reference information in the notes, do not waste time having students copy them (possibly incorrectly) from the lesson into their notes.

- Guided notes should record student learning, in their own words with their own work, as much as possible.

- Some step-by-step examples that match the lesson are good, but limit this as much as possible.

- Have students try steps on their own, before showing them on the board. This way students are reviewing their own work and thinking, instead of just copying.

- Leave a lot of white space.

- Provide space for learning that you didn’t plan to occur. You never know what connections students might make, or where they might get stuck.

- What is varied and what is identical.

- The sequence of the lesson and the sequence of the notes should match, perfectly.

- The quality and intent of questions and examples should be the same in the lesson and in the notes, but they do not have to be identical.

- Add practice instead of creating a separate assignment.

- Having worked out practice in the notes benefits students when they study or seek lost learning.

- Insert empty tables in the notes document. This allows students to have a place to write important information and keeps their notes organized and neat.

- If there is a good video or website that would help students with the topic, create a QR code to be embedded at the top of their notes. It’s a simple process, I prefer the website me. Simply copy the link to the video or site and paste it in the box on goqr.me, and a QR code is created. Simply paste it into the Word document and you’re done.