Group work and activities can be a lot of fun, and can be academically meaningful, for some students. Usually, those who need the support and intervention don’t benefit from the activities and group work as much as those who are already on the right track.

The problem is that group work is a double-edged sword, so to speak. On the one hand, students learn together, especially when the group wants to perform well. The trade-off is that socialization can cause the almost-got-it students to fail to gain the needed experience and understanding from the group activity.

I am a slow learner. I’ve been teaching for about two decades and just figured something out today about making group work meaningful for students that I’d like to share.

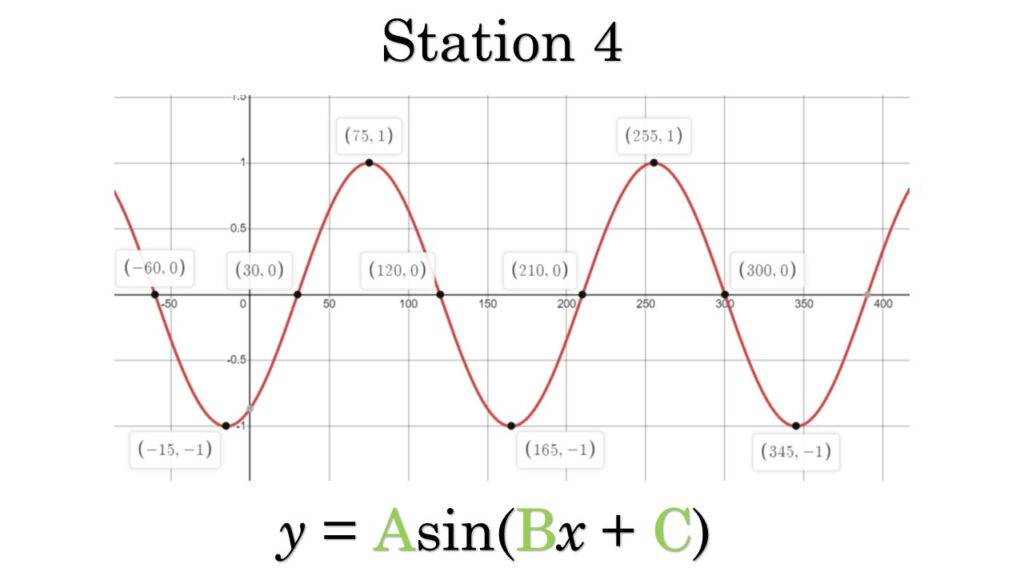

The IB students are learning about transformations of sinusoidal graphs like y = Acos(Bx + C) + D. I created a station/group work activity where 10 problems were posted around the room. In groups of four, students moved through each station and answered the questions posted there. A place to write the group’s answer is provided so that other groups can use the ideas of other groups as a jump-start, or can verify if the other group was correct. It’s a good activity and students feel more capable after completion.

In reality, most of them are not much better, if at all. In a group setting, the almost-got-it students often rely on those component and confident to do the risk-taking. Those decisions about how to start effectively and what information is most important to use and why, are actually the skills the almost-got-it students are lacking. They’re often satisfied with completing the process once the path to the solution is laid out for them. Figuring out the path is the hard part!

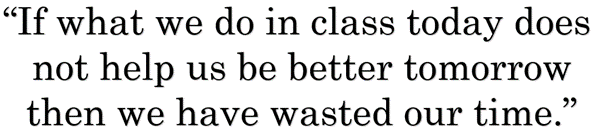

Today I made one small change. When introducing the activity, I shared a powerful quote mentioned rather off-the-cuff during a Cambridge IGCSE training. The speaker’s name eludes me at the time, darn brain. I did have the privilege of speaking with him again after that training and mentioned his quote. He didn’t remember saying it, but said it was worth writing down!

I mentioned to the students that if they weren’t better at the procedure and didn’t more deeply understand the concepts at the end of the activity, then it was a waste of time. And, who wants to waste time doing math?

The students, of course, agreed.

What is improvement? Students thought that being faster and more accurate would signify improvement.

Since there are two skills at play with the current material, I gave students two practice problems and a stop-watch (all projected on the board). Students had up to five minutes to complete the questions and were to write down their actual time when they finished.

At the end of the 5 minutes, I shared the solutions and students wrote down their score and time at the top of their paper.

After the little test-quiz, students completed the station activity and returned to their chairs for a second mini-quiz, to test if their efforts paid off.

I projected another pair of questions and started the stop-watch.

Students reported that they felt better prepared and claimed evidence of their improved preparation. However, this is what they often say without evidence. Soft, self-reported data is notoriously unreliable.

How students, especially the almost-got-it variety, engaged with the questions was different. They pressed the risk-takers and faster students to explain their thinking. Quite a few of the almost-got-it students even slightly separated from their groups to work on particularly troubling and challenging work independently before returning to verify and ask questions.